Dissecting A Decade-Long Writing Process With The Incendiaries Author R.O. Kwon

Author Rosalie Knecht Reimagines the Spy Game With Who Is Vera Kelly?

Match Made in Manhattan: 9 Questions With Playing With Matches Author Hannah Orenstein

Meet Dagger Imprint’s New Editor Chantelle Aimée Osman

In Orbit: 7 Questions With Artemis Author Andy Weir

By Caitlin Malcuit

Andy Weir shoots from Mars to the Moon in his latest novel Artemis, introducing us to a wealthy and exclusive lunar colony where Jasmine Bashara works as a porter, struggling to get by. There's not much money to be made in that gig, so Jasmine—“Jazz”—must survive and earn her keep as a smuggler. When a heist too good to pass up unearths a larger conspiracy, Jazz is thrown into the seedy underbelly of the glitzy Artemis.

Weir talked to me about the new and exciting setting for his story, his influences, and imparted some valuable advice for writers navigating the publishing world in the digital age.

Caitlin Malcuit: What is your process for writing a novel, especially the research that goes into science fiction?

Andy Weir: I start with a bunch of research. For me, the science and setting have to be right before I’m willing to work on the story. Once I’m into the actual writing, I set myself a daily word count to shoot for.

CM: Which authors influenced you?

AW: I’m a Gen-Xer, but I grew up reading my father’s sci-fi collection. So, despite my generation, my main influences are the Baby Boomer era authors. My holy trinity are Heinlein, Asimov, and Clarke.

CM: What drew you to setting Artemis on a lunar colony?

AW: I wanted to write a story about the first human settlement off of Earth. And I just really think that’ll be on the Moon. It’s so much close to Earth than any other celestial body. Most importantly, it’s close enough for trade and tourism.

CM: Jazz is certainly driven to survive, as Mark Watney was when he was stranded on Mars, but, given the wealth disparity on Artemis, what inspired you to tackle Jazz’s unique situation?

AW: Well I’ve always had a love of heist stories and crime novels. So I figured why not do a sci-fi heist story?

CM: Are you excited to see where Phil Lord and Chris Miller will take Artemis as they bring it to the screen?

AW: Absolutely! Though it’s still early days yet. I try not to get myself too worked up about it. A lot of things have to go right for a film project to be greenlighted.

CM: What advice do you have for aspiring writers, especially now that NaNoWriMo is in full swing?

AW:

- You have to actually write. Daydreaming about the book you’re going to write someday isn’t writing. It’s daydreaming. Open your word processor and start writing.

- Resist the urge to tell friends and family your story. I know it’s hard because you want to talk about it and they’re (sometimes) interested in hearing about it. But it satisfies your need for an audience, which diminishes your motivation to actually write it. Make a rule: The only way for anyone to ever hear about your stories is to read them.

- This is the best time in history to self-publish. There’s no old-boy network between you and your readers. You can self-publish an ebook to major distributors (Amazon, Barnes and Noble, etc.) without any financial risk on your part.

CM: Can you please tell us one random fact about yourself?

AW: I like to do woodworking. It’s a hobby that’s helpful to me to clear my mind when I’m stressed out or when I’m stuck on a plot problem in whatever project I’m on.

To learn more about Andy Weir, visit his official website, like his Facebook page, or follow him on Twitter @andyweirauthor. Also read our last interview with the author!

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

Dedication and Discipline: Sing, Unburied, Sing Author Jesmyn Ward On Writing

Jesmyn Ward (Photo credit: Beowulf Sheeha)

By Adam Vitcavage

Jesmyn Ward is the only author I think about on a weekly basis. Her stellar Salvage the Bones is the only novel I recommend to nearly everyone looking for a new book. If I don’t murmur the words, “Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones,” in any given week, then I at least think about how much her bleak and beautiful novel punched me in the stomach while simultaneously uplifting my spirits. Now, there’s a new novel from her I can suggest: Sing, Unburied, Sing.

I recently interviewed Ward, and I felt aspiring writers and readers of Writer’s Bone might find her comments about her writing process both encouraging and educational.

Adam Vitcavage: What excites you in the undergraduate writers you teach at Tulane University?

Jesmyn Ward: The writers who take my courses write across multiple genres. Some are writing YA, fantasy, or surreal literary novels. It just depends on the student. I love it all. What really attracts me to my students work and what makes me appreciate them is the passion that they have. I think that comes out in the work even if the work is not that polished or developed as it could be. That’s what I’m there for. I’m there to help them develop and polish it. Their passion for writing, telling stories, and creating worlds is what attracts me to their work.

AV: Once you get going with a draft for a novel, do you have a set writing process?

JW: I am a very linear writer. I work from the beginning to the end. I start at the first chapter and end at the last chapter. I don’t revise as I’m going because I feel if I stop to revise the things that I’ve written that I will get bogged down and will never complete the book. So I don’t revise and I just write straight through. I try to write for at least two hours a day for five days a week. Sometimes that is easier. I have two children, so when I have child support for them or when they’re in school is when it’s easier for me to do that. Sometimes I have to patch those hours together. I’ll wake up early and work for an hour then work for an hour later in the day when I have time.

I feel like the more disciplined I am about writing for two hours a day five days a week then the easier it is for me to access my creativity. I think it takes less time to sink into the world and to do the writing I need to do when it’s something I do five days a week. That’s how you write a book: it’s something you work at every day pretty regularly for at least a year if not a year and a half or two years. And that’s considered fast. I know some people take a decade on a book. I understand why.

It’s all about hours of dedication and discipline.

AV: Once you get the draft done, what does your revision process look like? What do you look for?

JW: The way that I revise is a little weird. I finish the first draft and then I let it sit for a month. I’ll work on other small things during that time and then I go back. I’ll read through the rough draft. Just read and take notes about things that need to be revised, changes that need to be made, things that can be cut or moved around, or whatever. I make a list and go through that list. I’ll concentrate on one thing on the list while reading through the draft. I devote an entire revision to just one aspect or one correction.

If I need to develop a character, then I’ll go through and develop a character throughout a revision. I’ll cross it off the list and go back again to concentrate on another aspect. My list can have 12 or 13 items on it. That list is just things I’ve noticed. If I went into a revision with the aim of correcting all thirteen of those things I feel I would miss something. It’s easier for me to focus on one thing through a revision. I revise twelve or thirteen times before I feel confident enough to show my work to a group of first readers.

First readers are just people that I’ve gone to school with, other writers I met at Stanford or Michigan. I’ll email them a draft and ask for their help. After a couple of months, they’ll give me suggestions and I’ll go back in and revise based on their feedback. That might take six or eight revisions. Once I’ve done that I feel confident enough that I won’t embarrass myself and I’ll send it to my editor.

And then [laughs] we revise for months. I mean, it is definitely a process. I’m the kind of writer who feels nothing is ever perfect when it’s fresh. The first rough draft is never perfect. I actually enjoy revision because writing that first rough draft is difficult. It’s different work because you’re creating this world and characters from nothing. It takes a different literary muscle than going back in and revising.

Revising is more enjoyable and more fun for me. I already have something, so at least I have the security of knowing I have something to work with on the page. Then it’s all about shaping. I enjoy knowing the security of just having to focus on making something better.

To learn more about Jesmyn Ward, follow her on Twitter @jesmimi. Read more of Adam Vitcavage’s work on his official website, or follow him on Twitter @vitcavage. Also check out Adam's full interview with Jesmyn Ward on The Millions.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

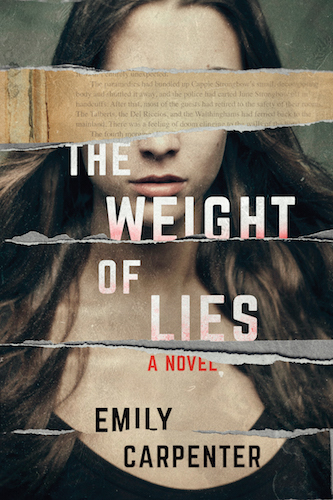

Worth the Weight: 11 Questions With Author Emily Carpenter

Emily Carpenter

By Lindsey Wojcik

The heat is on. By now, most of the country has experienced the familiar stickiness that comes with the summer season. The humidity has undoubtedly driven many to the beach or pool to cool off, and here at Writer’s Bone, no beach bag is complete without a sizzling new novel.

Emily Carpenter’s The Weight of Lies has all the makings of a classic beach companion. Vulture highlighted it as “an early entry in the beach-thriller sweepstakes.”

In her new book, Carpenter transports readers from New York City to a small, humid island off the coast of Georgia where Megan Ashley, the daughter of an acclaimed novelist, travels to discover more about her mother’s famous book, Kitten, for a tell-all memoir she has agreed to write. Kitten tells the tale of an island murder that fans believe may have been loosely based on a real crime. As the truth about where Megan’s mother, Frances Ashley, found the story for her infamous novel unravels, Megan must decide what is real and what is fiction.

Carpenter recently spent some time answering questions about transitioning from a career in television to writing novels, what inspired The Weight of Lies, and why it’s important for writers to appreciate their “customers.”

Lindsey Wojcik: You've been writing since a young age. What are your earliest memories with writing? What enticed you about storytelling?

Emily Carpenter: I’ve told this story a few times—the one about how I plagiarized The Pokey Little Puppy when I was 5. It’s my secret shame. I basically copied it word for word and illustrated it with crayons. I am not sure I actually finished it, so maybe I’m off the hook? After that, there were a couple of false starts on a novel about a girl with a horse when I was around 14. I’m not sure I had a handle on a coherent story, but I was definitely enamored by the idea of a girl (me) owning a horse. I absolutely lived for reading. I was an introvert, bookworm, a dreamer, and really imaginative. And while I didn’t really have a reference point for becoming an author, I was drawn to the whole world of storytelling.

LW: Who were your early influences and who continues to influence you?

EC: I read all of the Nancy Drew books, The Bobbsey Twins, The Hardy Boys multiple times over. Beverly Cleary and Laura Ingalls Wilder were early favorites. I loved those biography books with the orange covers, and there was another series where I remember reading about Madame Curie and Helen Keller. I read a lot of suspense books now because that’s the genre I write, but I enjoy all kinds of fiction. I’ve gone through periods when I read YA and literary classics, romance and horror. I’m really inspired by television writers right now. Noah Hawley, who writes “Fargo,” is immensely brilliant and funny. I also admire Ray McKinnon, a fellow Georgian, who wrote “Rectify.” Both those guys really inspire me.

LW: Tell us a little bit about your experience at CBS television’s Daytime Drama division. What did you do in that department? How did it influence your writing?

EC: I was the assistant to the director of daytime drama, so I basically answered phones, did paperwork, that kind of thing. I also read all the scripts for upcoming shows and wrote summaries for the newspapers to publish. I got to take contest winners on tours of the productions and assist with a couple of promo tapings of commercials for the shows. Once I took a bunch of contest winners and some of the actors to lunch because my boss couldn’t do it. I had the company credit card and had to pay for the whole thing, and it made me really nervous. I was, like 24, or something, and I’d never seen a check for a meal that big. In terms of influencing my writing, I think I really soaked up the concept of how to write tension and cliffhangers. “Guiding Light” and “As the World Turns” had some really talented writers on staff who were great at writing really funny, snappy banter, and I picked up on that—the rhythm of dialogue is so important and they were such masters at it.

I remember something my boss told me once when the writers had brought in a secondary character who was a part of this new storyline. So one Friday at the end of the show, they ended the final scene with a close up on his face. She got so mad about it and said, “You don’t end a really important scene—especially a Friday cliffhanger scene—on a day player!” She understood that, bottom line, the audience cared most about the core characters of the show. They loved them, not this random guy they’d brought in to be a temporary part of this new storyline. She knew that the show needed to leave the audience anticipating, thinking about those core characters all weekend long until Monday rolled around—not this day player. That really stuck with me, how important it was to understand who your audience was and what they wanted and giving it to them.

LW: You assisted on the production of “As the World Turns” and “Guiding Light.” Both of those soaps were on daily in my household growing up—three generations of women in my family, including myself, watched both shows, which are no longer on the air, and soap operas in general have been on the decline. What do you think influenced the change in daytime television?

EC: First of all, let me say, thank you for watching. I have a deep admiration and enduring fondness for those two shows. I watched them long after I left New York and moved back down South, and when they were cancelled, I cried. It really was such an end to an era. Although I’m sure there is an answer for why daytime TV changed, I’m not sure I know. I think, in the end, it’s probably to do with money, like everything else. And new technology and our capability to access streaming shows and binge watch really high quality programming. There’s no more appointment TV. We really have gotten out of the habit of showing up at a certain time to watch a show. I suppose the decline started with cable and cheap reality programming and TiVo. But I’m not sure what the deathblow was. And look, we still have four soaps running. I turned on “Days of Our Lives” the other day, and Patch and Kayla have not aged a whit since I watched them in the late ’80s.

LW: Tell us a little bit about your experience with screenwriting. What influenced your decision to change career paths from film production and screenwriting to writing novels?

EC: I was pretty naïve, hoping to break into the screenwriting business with zero entertainment connections or really any knowledge of the business at all. I think I had a good sense of story and structure in a general sense—I had some raw materials—but in terms of writing a kickass commercial feature, I wasn’t there. I didn’t know how to do it. And I think I was really sort of just learning the technique of writing as well. Learning how to write good sentences and evoking emotion with my words. I hadn’t majored in creative writing in school or even taken a single writing course in my life, I was just winging it. So really, it was audacious of me (or plain, old ignorant) to think I was going to write a spec screenplay that would sell to Hollywood.

But I just loved movies so much and writing and kept plugging away at it. I worked really hard and placed in a few contests, but ultimately couldn’t get an agent interested. After working on two indie productions with friends, I finally decided it was not going to happen. I took a break for a few years and hung out with my kids, enjoyed being a mom. Then one day, it suddenly occurred to me that there was this whole world of storytelling that I had overlooked. I started mulling over the idea of writing a book and researching the business side of publishing. It turned out to be much more accessible world. And I’ll say that my screenwriting experience, self-taught though it was, has formed the basis of my novel writing. I use a lot of the outlining and scene structuring tools that screenwriters use in my books.

LW: How did the Atlanta Writers Club guide you as a writer?

EC: They provided amazing access to a whole community of local writers, some of whom have become critique partners and dear friends. I found a critique group through them, which was where I read something I’d written out loud for the first time. And I attended several conferences the club sponsored and pitched my books to agents. I actually met my agent at one of the conferences.

LW: What inspired The Weight of Lies?

EC: I love classic horror books and films—Stephen King is just the master, of course. Carrie is one of my all-time favorites. One time I read that he had based aspects of Carrie on this girl he knew in school who was awkward and bullied by the other kids. That fascinated me, and I wondered if she ever found out what he did, what she would think of it. I mean, can you imagine? I get asked that question a lot, as an author, is my book based on real events or real characters? My books aren’t, but it intrigued me to imagine a writer who had the audacity to base her novel on a real murder and maybe even a real murderer, and so now there’s this eternal question out there among her fans about whether it was real.

LW: When you were writing The Weight of Lies, was there something in particular you were trying to connect with or find?

EC: Well, at the heart of the book, it’s really a story of this young woman who doesn’t feel like her mother has ever loved her or really even wanted her. And she’s so angry because she’s desperate to be affirmed and loved. She’s also a bit lost because she doesn’t have a whole lot going on career-wise, she hasn’t really been successful in the romantic department, and she’s getting older. She’s got a lot of resentment toward her mother to work through, but she’s really blinded by her pain. And her mother really is a monumentally self-centered diva, so there’s plenty of blame on both sides. That whole situation felt really compelling to me, that search to try to understand your mother as more than just the figure you rebelled against or had conflict with. Where you reach a crossroads at which point you have to decide whether you’re going to give your mother the benefit of the doubt and forgive her, or feed your childhood bitterness and hurt and go for the scorched earth option. Needless to say, Meg opts for earth scorching.

LW: How was the process of writing The Weight of Lies different from writing your debut Burying the Honeysuckle Girls?

EC: With Honeysuckle Girls, I had a lot of time. A lot of freedom. I was 100 percent on my own timetable. Then, once I signed with my agent and went on submission, it became a process of listening to my agent’s opinions and the opinions of the marketplace and deciding what to pay attention to and what to bypass. The great thing was that I had a lot of time to tinker with the book, which is a luxury. It wasn’t that much different writing The Weight of Lies because I didn’t sell the book until I had completed it. My next books, though, were sold on pitch, so that’s been an entirely new process, to deliver something you’ve already been paid for.

LW: What’s next for you?

EC: I’m writing my next book, which is about a young woman with a secret she’s kept since her childhood, who agrees to accompany her husband to an exclusive couples therapy retreat up in the mountains of north Georgia so he can get help for the nightmares that have been plaguing him. And then things start to go sideways, and she realizes that nothing at this isolated place is as it seems.

LW: What’s best advice you’ve ever received and what’s your advice for up-and-coming writers?

EC: My agent told me once, “Remember, this is your career…” I can’t even recall what we were talking about exactly—it might’ve been a deadline, or what I was going to write next—but the point was, she wanted me to clear away all the noise from other people’s expectations and do what was best for me. To follow my heart. It was just what I needed to hear at the moment, especially because I have the tendency to go overboard to make other people happy and overlook what’s in my own heart. It really settled me down and gave me the confidence to go forward.

I think one of the things I’d like to remind up-and-coming writers is that they are getting into a business and many of the decisions that editors and publishers make have to do with money. So when new writers encounter perplexing situations, I think they need to understand that financial bottom line motivates many of them. It’s sometimes a bitter pill to swallow, but it’s reality. And as writers, we have to be able to nurture our art in that atmosphere of commercialism.

The other day I heard Harrison Ford say in an interview that he doesn’t like to call people who see his movies “fans,” but “customers.” It was a really pragmatic, non-romantic way for an actor or artist to view what they do, but it did sort of speak to me because I tend to lean toward being really practical. I do see the artistic side of writing, and I can get really swept up in the magic of creating characters and a story. On the flip side, I also do really appreciate my “customers,” and I consider it an honor to have the opportunity to entertain them. And I think what the customers wants and expects should matter to writers. It’s not the end-all, be-all, but it is something to keep in mind.

To learn more about Emily Carpenter, visit her official website, like her Facebook page, or follow her on Twitter @EmilyDCarpenter.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

Exploring the Human Animal With Crime Fiction Novelist Nick Kolakowski

Nick Kolakowski

By Sean Tuohy

Author Nick Kolakowski loves crime fiction. From his work with ThugLit, Crime Syndicate Magazine, and his upcoming novel A Brutal Bunch of Heartbroken Saps (out May 12), it’s easy to tell that the author truly values the hardboiled crime-fiction genre and knows how to write it well.

Kolakowski sat down with me recently to talk about his love for the genre, the seed that created the storyline for his new novel, and “gonzo noir.”

Sean Tuohy: What authors did you worship growing up?

Nick Kolakowski: I always had an affinity for old-school noir authors, particularly Raymond Chandler and Jim Thompson. What I think a lot of crime-fiction aficionados tend to forget is that a lot of the pulp of bygone eras really wasn’t very good: it was all blowsy dames and big guns and writing so rough it made Mickey Spillane look like Shakespeare. But writers like Chandler and Thompson emerged from that overheated milieu like diamonds; even at their worst, they offered some hard truth and clean writing.

ST: What attracts you to crime fiction, both as a reader and a writer?

NK: I feel that crime fiction is a real exploration of the human animal. You want to explore relationships, pick up whatever literary tome is topping the best-seller lists at the moment. You want a peek at the beast that lives in us, crack open a crime novel. As a reader, it’s exciting to get in touch with that beast through the relatively safe confines of paper and ink. As a writer, it’s good to let that beast run for a bit; I always sleep better after I’ve churned out a lot of good pages.

ST: What is the status of indie crime fiction now?

NK: I’d like to think that indie crime fiction is having a bit of a moment. A lot of indie presses are doing great work, and highlighting authors who might not have gotten a platform otherwise. Crime fiction remains one of the more popular genres overall, and I’m hopeful that what these indie authors are producing will help fuel its direction for the next several years.

Not a whole lot of authors are getting rich off any of this, but writing isn’t exactly a lucrative profession. There’s a reason why all the novelists I know, even the best-selling ones, keep their day jobs. We’re all in it for the love.

ST: What is your writing process? Do you outline or vomit a first draft?

NK: I keep notebooks. Over the years, those notebooks accumulate fragments: sometimes a line of two I’ve overheard on the subway, but sometimes several pages of story. Usually my novels and short stories start with a kernel of an idea, and I start writing as fast as I can; and as I start building up a serious word count, I begin throwing in those notebook fragments that seem to work best with the scene at the moment. It’s a haphazard way of producing a first draft, and it usually means I’m stuck in rewrite hell for a little while afterward as I try to smooth everything out, but it does result in finished manuscripts.

I simply can’t do outlines. I’ve tried. But outlining has always felt very paint-by-numbers to me; once I have the outline in hand, I’m less enthused about actually writing. But I know a lot of other writers who can’t work without everything outlined in detail beforehand.

ST: Where did the idea for A Brutal Bunch of Heartbroken Saps come from?

NK: A long time ago, I was in rural Oklahoma for a magazine story I was writing. It was early February, and the land was gray and stark. Near the Arkansas border, I saw a Biblical pillar of black smoke rising in the distance; as I drove closer, I saw a huge fire burning through a distant forest. This would be a really crappy place for my car to die, I thought. It would suck to be trapped here.

So that real-life scene rattled around in my head for years. Eventually I began depositing other figures in that landscape—Bill, the elegant hustler, based off a couple of actual people I know; an Elvis-loving assassin; crooked cops—to see how they interacted with each other. The result was funny and bleak enough, I thought, to commit to full-time writing.

ST: You referred to A Brutal Bunch of Heartbroken Saps as “gonzo noir.” Can you dive into that term?

NK: I love crime fiction, but a lot of it is too serious. That seems like an odd thing to say about a genre concerned with heavy topics like murder and misery, but more than a few novels tend to veer into excessive navel-gazing about the human condition. As if injecting an excessive amount of ponderousness will make the authors feel better about devoting so many pages to chases and gunfire.

But real-life mayhem and misery, as awful as it can be, also comes with a certain degree of hilarity. You can’t believe this dude with a knife in his eye is still prattling on about football! A reality television star might dictate whether we end up in a thermonuclear war! And so on. With gonzo noir, I’m trying to blend as much black humor as appropriate into the plot; otherwise it all becomes too leaden.

ST: Your main character, street-smart hustler Bill, is on the run from an assassin and finds himself in the deadly hands of some crazed town folks. Why do writers, especially in the crime fiction genre, like to torture their characters so much?

NK: Raymond Chandler once said something like: “If your plot is flagging, have a man come in with a gun.” I think a lot of current crime-fiction writers have a variation on that: “If your plot is flagging, have something horrible happen to your main character. Extra credit if it’s potentially disfiguring.” It’s an effective way to move the story forward, if done right, and how your protagonist reacts to adversity can reveal a lot about their character through action.

Done the wrong way, though, it becomes boring really quickly. Take the last few seasons of the TV show “24.” Keifer Sutherland played a great hardboiled character, but subjecting him to the upteenth gunshot wound, torture session, or literally heart-stopping accident got repetitive. When writing, it always pays to recognize the cliché, and figure out how to subvert it as effectively as possible—the audience will appreciate it.

In A Brutal Bunch of Heartbroken Saps, Bill has done a lifetime of bad stuff. He’s ripped people off, stolen a lot of money, and left more than a few broken hearts. I felt he really needed to really pay for his sins if I wanted his eventual redemption to have any weight. Plus I wanted to see how much comedy I could milk out of a severed finger (readers will see what I mean).

ST: What’s next for you?

NK: I’ve been working on a longer novel (tentatively) titled Boise Longpig Hunting Club. It’s about a bounty hunter in Idaho who finds himself pursued by some very rich people who hunt people for sport. I’ve wanted to do a variation on “The Most Dangerous Game” for years, and the ideas finally came together in the right way. It’s an expansion of my short story, “A Nice Pair of Guns,” which appeared in ThugLit (a great, award-winning magazine; gone too soon.)

ST: What advice do you give to young writers?

NK: A long time ago, the film director Terrence Malick came to my college campus. He was supposed to introduce a screening of his film “The Thin Red Line,” but he never set foot in the theater—unsurprising in retrospect, given his penchant for staying out of sight. However, he did make an appearance at a smaller gathering for students and faculty beforehand.

All of us film and writing geeks, we freaked out. Finally one of us cobbled together enough courage to actually walk up to him and ask for some advice on writing. He said—and you bet I still have this in a notebook—“You just have to write. Don’t look back, just get it all out at once.”

I think that’s the best advice I’ve ever heard. It’s easy to stay away from the writing desk by telling yourself that you’re not quite ready yet, that you’re not in the mood, that somehow the story isn’t quite fully baked in your mind. If you think like that, though, nothing is ever going to have to come out. Even if you have to physically lock yourself in a room, you need to sit down, place your hands on the keyboard, and force it out. The words will fight back, but you’re stronger.

ST: Can you please tell us one random fact about yourself?

NK: I like cats and whiskey.

To learn more about Nick Kolakowski, visit his official website or follow him on Twitter @nkolakowski.

The Writer's Bone Interviews Archive

YA Author Tammar Stein Searches for a Hero in The Six-Day Hero

Tammer Stein

By Lindsey Wojcik

Nearly 50 years ago, Israel and the neighboring Arab states fought in what is now known as the Six-Day War. Just in time for the 50th anniversary in June, young adult author Tammar Stein's The Six-Day Hero will officially be released (it is currently available on Amazon).

While The Six-Day Hero is not directly about the conflict, it does aim to transport readers to the sounds, sights, and events of West Jerusalem during that time. The story follows 12-year-old Motti, a boy who dreams of being a hero, and thinks the only way to become one is by being a soldier like his older brother (who serves in the Israeli army).

Stein, the daughter of Israeli Defense Force soldiers, recently talked to me about her writing process, what inspired The Six-Day Hero, and her advice for other authors.

Lindsey Wojcik: What made you want to pursue writing, specifically young adult fiction?

Tammar Stein: I love books, the physical feel of them, the look of them, the way that they’re gateways to making connections and getting lost in adventures. Even as a young child, I remember my mother scolding me to go outside and get some fresh air because I had been inside reading for hours. It felt inevitable for me to try and create that same kind of magic for someone else.

I never set out to write for young adults, but when my agent read my manuscript for Light Years, she felt it could be a great young adult title. The character was 20 years old; it never crossed my mind that that could be a YA title. But the themes were classic YA: figuring out who you are, who you want to be. We got great response from the YA editors and I never looked back.

LW: What is your writing process like? How has it evolved over time?

TS: My writing process used to be: sit, write, delete, and repeat 50 times. This is not the most efficient way to write a novel. Light Years, my first book, took me five years to write. It turns out that just because I knew a great book when I read it, didn’t mean I could just write a great book myself. My second novel, High Dive, was also kind of a pain to write. I wrote the whole draft of it, almost 300 pages, before realizing it just didn’t have that magic spark. And I started back on page one.

By my third novel, Kindred, I wised up. I outlined. Now I do that for all my books. Not necessarily a detailed breakdown of each chapter, but a strong, two-page outline so I don’t get lost getting from the beginning to the end. It’s harder than it sounds, but it’s helped me so much.

LW: What kind of research went into outlining and writing The Six-Day Hero?

TS: The first thing I did was read. Other than the fact that it lasted six days, I really didn’t know much about the war. So I read dozens of books on the subject. I read newspaper articles from the time period. I watched documentaries. I'm also the daughter of Israeli Defense Force soldiers, and once I had a good sense of the events, I started interviewing Israelis who had experienced the war. Some as soldiers, some as children. I ended up speaking with half a dozen Israelis, including my parents, whom I pestered on a weekly basis for more details.

LW: What made the Six-Day War an intriguing and important topic for you to write a fictional story about?

TS: In 1967, Israel teetered between existence and annihilation. By winning the Six-Day War, it averted annihilation…and began the modern dilemma of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. This summer (June 5-11) marks the war’s 50th anniversary.

The West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and the Jewish Settlements are constantly in the news. If you’ve ever asked yourself, “How in the world did we get into this hot mess?,” the answer is, the Six-Day War. That’s the war that started all this. This is a 50-year-old hot mess. In this book, I look at the history of the war through the eyes of the people living through it. And it's the first English book for younger readers set during the Six-Day War, giving context and perspective to the complexity the world is still trying to solve. I do believe this is a situation that will be resolved one day. We will move on. We will find a way for all these millions of people to live in peace with one another. But to do that, we have to understand how it got started.

You cannot shape the future without knowing the past. But because there are so many hard feelings, because people are tired of constantly hearing about the same conflict, there’s this tendency to just want to move on, to ignore it. Especially when it comes to kids. So there’s no one writing about it, no one publishing about it. And kids are just left in this vacuum. They hear the news, but they don’t have any basis for truly understanding it. I wanted to change that.

To be clear though, the book is not about the war. The book is about Motti, a 12-year-old boy, who wants to feel heroic. But when you read the book, you learn about the history of the war through his eyes. The violent details of war didn’t strike me as the best way to tell a kids’ story. Rather, I wrote a book about the struggles of a 12-year-old, struggles shaped by the same forces that shaped the war. I hope the book will transport young readers to the sounds, sights, and events of West Jerusalem 50 years ago.

LW: What inspired you to write it from a 12 year-old’s point of view?

TS: Motti just came to me. It’s one of the moments that felt almost mystical. I just had this scene pop into my mind: a restless, bored kid forced to sit through an assembly, desperate to get away. Motti is a scrappy boy, always looking for mischief and fun. He struggles to shine in the big shadow cast by his successful older brother, Gideon. Straight-arrow/Gideon is now a soldier in the Israeli army, and Motti is equally proud and jealous. Over the course of the next month, everything Motti knows about Israel, his brother, and himself will be put to the test. He will realize that war is not a game, and he will face harsh challenges to be the hero he always dreamed of.

LW: The Six-Day Hero will be officially released in time for the 50th anniversary of the war. How does the book honor its history?

TS: When you hear that something happened 50 years ago, there’s this reflexive feeling that it’s ancient history. That it barely matters. But I spoke with people who lived it, fought through it, and are still haunted by what happened. The whole world is still being shaped by what happened. It’s far from ancient history, and I wanted to make sure that there was something there for kids to connect to.

LW: What's next for you?

TS: The Six-Day War was just one in a chain of wars for Israel. The history of an Israeli family can really be told by tracing the family’s lives through the wars they fought. Six years later was the Yom Kippur War, and my next book is about Beni, Motti’s younger brother, with the Yom Kippur War as the setting.

LW: What's your advice for aspiring authors?

TS: My best piece of advice is to try to balance a sense of urgency with lots of patience. Both are absolutely necessary to write a book. If you don’t feel urgency, you’ll never write. It’s always much nicer to plan to do it later, in the evening, tomorrow morning, over the weekend. If you don’t feel urgency, you’ll always put it off. But you have to be patient with yourself and your work as well. Your first draft will be terrible. Your sense of urgency will shout at you to share it with your family and friends, to start sending it out to agents, to publish it as an e-book. Don’t do that. You need to go back and revise. Then you let it sit for a month (or three) and come back to it with fresh eyes. And just as you get comfortable with your patience and want to keep tinkering with your manuscript forevermore, your sense of urgency needs to rise up again and urge you to send it out and share it with the world.

To learn more about Tammar Stein, visit her official website, like her Facebook page, or follow her on Twitter @TammarStein.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

A Conversation With Girl Through Glass Author Sari Wilson

Sari Wilson

By Adam Vitcavage

Editor’s note: this interview originally appeared on www.vitcavage.com, shortly before Girl Through Glass was originally released in January 2016. You can now purchase the novel in paperback.

Sari Wilson’s debut novel was about a decade in the making. Wilson’s head was filled with images from her childhood as a ballerina: her hair up in a tight bun, blistered feet, and countless leotards. She knew she wanted to write about the world she spent so much time in, but, more importantly, wanted to write about the emotional truth of her time training in ballet and her childhood.

The story grew and grew and became the fanciful novel Girl Through Glass. In the debut, a young rising star in the 1970s ballet world meets a shadowy middle-aged man named Maurice who becomes fascinated with her. In the present, a dance professor deals with her past as a dancer, and must confront what happened to her all of those years ago.

I spoke over the phone with Wilson for what was, according to the author herself, her first interview as an author.

Adam Vitcavage: I know this book came about after you had thought of a short story about ballet. Can you talk about the genesis of how this book came to be?

Sari Wilson: It was a long process. I would say 10 years or more, depending on how you count. I got the image of these girls—which actually became one of the first images in the novel—these young girls putting on their leotards and tights like they’re putting on armor, getting ready for battle. That image came back to me very strongly. It was from my childhood, but I hadn’t thought of it in many years.

It was emotionally powerful to me, but I didn’t know what to do with it. I tried to make it into a short story. It never worked. It just kept getting bigger and bigger. It was so different than anything I had been writing at the time.

I had my own experiences as a young girl in the ballet world that wasn’t so different than a lot of girls’ experiences. I felt that I touched on something that was related to the time period too. New York City, the late 1970s, the early 1980s, all of those Russians. Even though I never studied with the Russians, they were everywhere.

I became very fascinated with all of this, in a writerly way. I went back to the material in that capacity. I interviewed people whom I danced with. I read a ton. That’s when these characters started emerging. They took me over. The girl Mira came first. Her story is not mine, but it’s informed by my experience—people I knew, places I danced. I came to really love her and feel for her. I feared for her, but I had to follow her story until the end. I actually wrote the whole Mira storyline first. The character of Kate came later. I added Kate because I felt it needed an adult frame. She’s a very complex character. I learned—as I wrote—that they were the same person.

AV: So, you didn’t intend for them to be the same person. How and when did you decide that they needed to be the same?

SW: I already had the structure of the book. My job became figuring out who this Kate character was and what her story was. Especially how it related to Mira’s story.

AV: As I was reading the book, it became fascinating to me about how this lovely girl became this fraught middle aged woman.

SW: Yes, it became an exploration into the past. Can we ever escape from our past? How does it transform us?

AV: Speaking of the past. You say that you “stole liberally” from your childhood. How many experiences of yours found their way into Mira’s life?

SW: A lot of the setting was taken from my childhood. For example, the New York City blackout in 1977. I remember that very distinctly. A lot of the description of the ballet studios I danced in. I loved these spaces–they were windows into other worlds. A lot of the girls were based on girls I knew and danced with.

Many of the images and the feelings are drawn from my childhood. Mira’s emotional truth is my emotional truth. Her emotional experiences in the dance world were mine. At the same time, pretty much everything that happens to her is fictional.

AV: How did a character like Maurice come into Mira’s life?

SW: He is completely a fictional character. There was no Maurice in my life.

AV: But are there these types of men who are interested in these young girls? Or was that completely fictional?

SW: Historically, there have been men like this in the ballet world. There are passionate fans known as balletomanes. Ballet lore is filled with balletomanes—and examples of the extremity of their passion for this ballerina or that ballerina. If you look at the [Edgar] Degas ballet paintings, there’s often a shadowy figure. A man, shadowy and hiding behind the curtains.

Maurice is also drawn from some storybook characters. I wanted the book to have some element of a fairytale-feeling in terms of tone. Maurice came out of that. The ballet world is filled with this idea of the mysterious lurking man, and also these passionate, often obsessive balletomanes. To me, Maurice came as part of that world: the story of ballet.

In my life: there were not these men. But, I will say that to be a dancer means to always be watched. There were always people coming into the classrooms and we never knew why. They’d be standing and watching us with clipboards and then whispering and leaving. As I was remembering this world and my childhood experiences, I also remembered girls were chosen for roles in this way. Things happened because you were seen. You didn’t have a voice as a young dancer; only your body. Your body was everything.

AV: It’s just crazy to hear about these types of people. There were moments in the book that were left up to the reader’s imagination. Why was it important to leave out some details?

SW: I would say there were probably 1,000 pages that aren’t in the book—edited out over the years.

AV: That’s fascinating. I wanted more, but I’m not sure I know what I wanted of. I mean this as a compliment. I just needed more of these characters.

SW: I write from images. I write setting and characters, and the plot comes with me later. I have to throw out a lot of what I generate. One of my professors in graduate school was Tobias Wolff. Working with him taught me something about the art of leaving things out. How when you leave something out, you can create more tension and more mystery.

AV: I definitely felt that tension.

SW: I worked a lot in the later stages on the structure. How to create dramatic tension by withholding information. That was always a question I asked myself. Maybe I left out too much in the end. I don’t know. I’m going to need my readers to tell me.

AV: I appreciated the tension. I wanted these characters in my life. I need to read more about ballet because of this book.

SW: That’s awesome. I could not be more thrilled to have someone who basically didn’t know anything about ballet being captured by the mystery of it—as I was as a child. It’s a strange world, it’s a dangerous world, it’s a magical world, and largely it’s a province of girls. I’m thrilled a man would find it compelling.

AV: I read your opinion piece for The New York Times about how it is a dangerous world.

SW: I actually think it’s a good moment for ballet right now. In terms of mainstream culture at least. Misty Copeland is someone everyone is so excited about. She’s a revolutionary dancer who is really shaking things up. Then there’s also a [television show on Starz] called " Flesh and Bone" that covers a lot of the same themes as my novel.

But as much as this book is about ballet, I wanted to write a book about the human condition. Not just a ballet book. I wanted to find what was compelling and tragic and deeply human in all of these characters—and set it in the world of ballet.

AV: You did a good job with these characters. I know nothing about ballet, but I completely understood that attention that Mira wanted. Other than that human connection and the building of tension, what other things do you try to implement stylistically into your writing?

SW: I think my style comes from a lot of years of very hard work. I write a lot, but I haven’t published that much. That’s because I have to be really honest with myself. Am I putting on paper what is absolutely true? Is it the emotional truth? If it’s not then I have to keep going. I do a lot of freewriting, and then I edit most of it out. What remains is the writing that has the most energy and speaks to me the most.

It’s images and character’s voices that come to me first. I do a lot of writing to find who these people are and to figure out where they’re coming from. Then my job becomes the story. Putting everything together is actually the last piece for me. It’s a layered process.

AV: So what’s a normal writing day for you?

SW: Usually, I start where I left off. I leave a note for myself about what questions I have. I usually start out doing free writing to get underneath my conscious mind. When I start to surprise myself is when I think something is moving and interesting. If I’m just trying to generate material, my goal will be a certain number of pages in a day or a session. If I’m in the editing process, I’ll give myself a similar goal of pages to edit.

AV: Are you already onto processing the next project? Hopefully, it’s not another 10-year process for you.

SW: I hope it’s not another 10 years (laughs). I started another one. I started it last spring, and I’m very excited for it. I’m trying to do more advanced planning for this one so it doesn’t take as long. Doing more outlining ahead of time, though I’m sure it will be another layered process.

AV: Can you talk about anything of the book? The characters or emotions you’ve come up with.

SW: I really can’t. It’s too early. I just have some characters and some situations. But it’s too early.

AV: I totally get it. Is that all you’re working on, or do you have any short stories or essays?

SW: I am working on some essays related to the book and ballet. As far as short stories: not at the moment. I’m really compelled by the novel form. I think it has a lot of energy right now.

AV: What about comics at all? I know your husband is a cartoonist.

SW: My husband is a cartoonist, his name is Josh Neufeld, and we are publishing an anthology of linked short stories and comics this spring. It’s called Flashed: Sudden Stories in Comics and Prose. It’s all flash fiction. Some of it is prose and some of it is comics. They’re all in dialogue with each other. There are some great comics and great fiction writers involved. We loved putting them together.

To learn more about Sari Wilson, visit her official website, like her Facebook page, or follow her on Twitter @sariwilson.

Read or listen to more of Adam Vitcavage's interviews by visiting his official website or subscribing to his podcast "Internal Review."

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

Imagination On Fire: 10 Questions With Author Joe R. Lansdale

Joe R. Lansdale

By Sean Tuohy

Joe R. Lansdale is a writer’s kind of writer. I don’t think there’s a storytelling medium he hasn’t worked in. He’s penned 30 novels, most of them taking place in his home state of Texas. He’s also worked on comic books, television shows, films, and newspapers.

Lansdale’s stories are filled with strange, yet relatable characters. His stories are original and fast- paced. Lansdale grabs his readers quickly and pulls them into a world created by a master storyteller.

Recently his novel Cold In July (a personal favorite we featured in “Books That Should Be On Your Radar” in March) was produced into an award-winning film starring Don Johnson, Michael C. Hall, and Sam Shepard. His long-running Hap and Leonard series has also been turned into a TV series.

Lansdale took a few minutes to chat about the craft of storytelling, how he works in so many different mediums, and his new publishing house Pandi Press.

Sean Tuohy: When did you decide you wanted to become a storyteller?

Joe R. Lansdale: I was four when I discovered comics. I wanted to write and draw them. By the time I was nine, I realized I liked writing, but didn't really have the talent to draw. Stories, novels, and TV shows, movies influenced me as well. So pretty much all my life.

ST: Who were some of your early influences?

JRL: Jack London, Twain, Rudyard Kipling, and Edgar Rice Burroughs are a few. Burroughs really set my youthful imagination on fire. I wanted to be a writer early on, but when I read him at eleven years old, I had to be.

ST: What is your writing process like?

JRL: I get up in the morning, have coffee and a light breakfast and go to work for about three hours. That's it. I do that five to seven days a week. Now and again I'll work in the afternoon at night, but that's mostly how I do it day in and day out. I polish as I go and try to get three to five pages a day, but sometimes write a lot more.

ST: You have written for TV, film, and comics. Does your process or writing style change between the three formats?

JRL: Well, the format is the change, but you always write as well as you can, and you write to the strengths of the medium. Each as different, but you try and do them all as well as you can. I find I sometimes need a day to get comfortable doing something other than prose, but then the method comes back to me, and I'm into it.

ST: Your novel Cold in July was turned into a film and your long running Hap and Leonard series was turned into a TV show. How does it feel to see your work translated into another form?

JRL: It's fun, but always a little nerve-wracking. You always see stuff they left out, or changed, but my experiences so far have been really good. Enough things get made, I'm sure to have one I really hate. But again, so far, way good.

ST: Recently you opened Pandi Press with your daughter Kasey (a talented singer). What is the goal of this new publishing house?

JRL: To publish some of my work that's out of print, and to make the money that the publisher would end up with if they reprinted. It's an experiment as well. We'll see how it turns out. I plan to do some original books there as well.

ST: Being from Texas the Lone Star State plays a big part in your stories. What is it about Texas that makes it such an interesting backdrop filled with interesting characters?

JRL: You said it. It's full of interesting characters. But the main reason is it's what I know well, and I can write about it with confidence.

ST: What is next for Joe Lansdale?

JRL: More novels, short stories, films, and comic adaptations of my work by others.

ST: What advice do you give to first-time writers?

JRL: Read a lot, and put your ass in a chair and write. Only two things that really work.

ST: Can you tell us one random fact about yourself?

JRL: I have been studying martial arts for 54 years.

To learn more about Joe R. Lansdale, visit his official website, like his Facebook page, or follow him on Twitter @joelansdale.

The Writer’s Bone Interviews Archive

A Woman of Words: 10 Questions With Author Lynn Rosen

Lynn Rosen

By Daniel Ford

Lynn Rosen’s debut novel A Man of Genius has all the hallmarks of a hit: an unreliable, playboy narrator, well-written suspense, and, of course, a murderous plot.

Rosen revealed to me that she considers herself more of a storyteller than a writer, and from what I’ve read so far of A Man of Genius, she’s far too modest in her self-assessment. There’s an old school charm and elegance to her prose—perhaps owing to her “long years of a rich life”—that speaks to a confidence authors more than half her age have trouble conjuring.

The octogenarian author talked to me recently about her writing rituals, tips for becoming a storyteller, and what inspired A Man of Genius.

Daniel Ford: Did you grow up wanting to become a writer or did the desire to write grow organically over time?

Lynn Rosen: I didn’t grow up wanting to become anything—except to simply grow up. In my youth, which was many years ago, little was expected of females outside of marriage and motherhood. My desire to write grew from loneliness and finding that those who populated the stories in my mind were great listeners and, best of all, served me better than the dolls I played with, for the characters in my mind were much fuller and more malleable.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

LR: My earliest influence was Inez Haynes Gillmore Irwin, a feminist and political activist who, in the early to mid-20th century, wrote a series titled “Maida’s Little Shop.” Maida has been paralyzed, but with great effort has recovered the use of her legs. Acknowledging her efforts, her loving wealthy father gives her all her heart desires, including a little toy and trinket shop. At the time I met Maida, I was unable to walk as a result of paralytic polio. Maida drew me to a very early realization of the power of literature: the worlds it draws you into, its ability to disclose life’s possibilities, and the mirror it holds up to your own life.

After Irwin, Daphne duMaurier, Charlotte Bronte, Jane Austen, and Laurence Sterne grabbed my attention. DuMaurier and Bronte for their application of the Gothic with its use of the sublime, Austen for her enviable ability to frame a social scene, and Sterne for his awesome control of plot and time lines.

DF: What’s your writing process like? Do you outline, listen to music, etc.?

LR: I do listen to music as I write—in fact one particular piece of music, a disc titled “The Memorable & Mellow Bobby Hackett.” I play, replay, and replay it, over and over again. I’m a very slow writer.

DF: How did you develop your voice? Are you able to slip into it during the writing process or is it something you find while you’re editing?

LR: My voice was established early in the process of writing A Man of Genius. It emerged from my need to develop the work from the outside in—from its binding theme to plot, and character development, which, I hoped, would sustain the theme and contribute to a sense of an organic whole.

DF: What’s the premise of A Man of Genius and what inspired the novel?

LR: The premise of the novel is a series of overarching questions that focus on our relationships with our personal human idols. Who do we elect to revere? What is our criteria for selection? How much of our idols’ foibles are we willing to forgive? All of this inquiry was initiated and sustained by a very old memory of an unexpected meeting I had with Olgivanna Wright at Taliesin, when I was a young undergraduate. For many years I wondered why that particular memory stayed with me. In time, I began to realize the binding force that sustained it was the question of personal idolatry, and what that idolatry says about the idolater. Years passed, during which the memory took on new forms and new perceptions—as memories do. Finally, it emerged in its new form as A Man of Genius.

DF: How much of yourself ended up in your characters? How do you develop your characters in general?

LR: Little of myself ends up in my characters. I develop and move my characters always in support of the over-arching theme that drives the novel.

DF: The unreliable narrator has become a literary trend the last couple of years. What made you decide on that convention, and how did you make your story unique?

LR: I believe all narrators are unreliable; few openly admit their biases, though they usually emerge in time. I believe that the unresolved ending of A Man of Genius demands an unreliable narrator aware of his limitations. If the narrator were presented as reliable, the alternate possibilities that run through the story line would not be sustainable.

DF: What were some of the themes you wanted to explore in the novel?

LR: Idolatry and forgiveness are the major themes. What I wanted most was to bring the readers to a point where exploring the book’s themes resulted in an exploration of the reader’s own systems of moral obligation.

DF: How’s it feel to publish your first novel at age 84, and what was your publishing journey like?

LR: I never thought of myself as a writer—in fact, to this day I haven’t reached that stage of self-identification. I think of myself as storyteller. I love a good story and enjoy sharing one with others. I began writing in my pre-teens during World War II. With my father away in the service, I had a great deal to say and nobody would listen, so I wrote letters to the editor of The New York Times and some were printed, and people began to listen and write back through the paper. Then there were articles about books I read, and some of those also were printed—a short story was published and I wrote several drafts of novels that now sit snugly in files in my office. Perhaps they’ll now see the light of day because I’m beginning to think I just might be a writer. I believe that, whatever one accomplishes in life has little to do with age, and everything to do with attitude. If anything, long years of a rich life, as mine was and is, expands a writer’s possibilities. In the end it all resides in the mind and spirit.

DF: What’s your advice to aspiring authors?

LR: Don’t decide to become a writer and then go poking about looking for a story. Discover a story that you find compelling and become a writer.

DF: Can you please tell us one random fact about yourself?

LR: In my mind I’m 33 years of age. I’ve been frozen there for a very long time. Don’t ask me why. Personally it wasn’t a particularly outstanding year.

To learn more about Lynn Rosen, visit her official website, like her Facebook page, or follow her on Twitter @authorlynnrosen.

The Writer's Bone Interviews Archive

The Zen of Storytelling: 11 Questions With Author Amy Parker

Amy Parker

By Daniel Ford

Amy Parker’s debut short story collection Beasts & Children includes a blurb all writers would kill for:

Amy Parker proves herself an unflinching, passionate, and profoundly humane writer, even as she hold a knife to your heart.”—Michelle Huneven, author of Blame

After my discussion with the author, I couldn’t agree more. The first thing I look for when reviewing fiction is whether or not there’s a big ol’ thumpin’ heart behind the prose, and Parker’s literary EKG is off the charts. She expertly drops readers into a fully formed world in her first sentence and explores familiar family themes throughout her linked stories.

Parker recently talked to me about how an English sheepdog sparked her creativity, why authors need to finish their stories, and what inspired Beasts & Children.

Daniel Ford: When did you decide you wanted to be a writer?

Amy Parker: In third grade my teacher held a contest—whoever wrote the most stories in a marbled black composition book class would win a prize. The prize was a poster of an English sheepdog set against a very, very blue sky. I wanted that poster! You know how it is when you’re eight, and you think something is so cute that you could die? That desire for cuteness—to possess that which is adorable. That dog—textbook old English sheepdog, pink tongue hanging out, shaggy-browed, panting under an improbably blue sky. My soul cried out for it. So I cranked out a dozen stories—derivative as hell—baby’s first potboilers—one of them involved me having an affair with Superman and getting into a catfight with Lois Lane, for example. Some I illustrated. I busted my butt. That was also the first time I encountered the problem of the blank page—and the pain caused by lack of narrative invention. But I won the poster. And I still have the notebook.

DF: Who were some of your early influences?

AP: How early? I loved Lois Duncan, in particular the book Down a Dark Hall; I also read Stephen King and John Irving probably far too early. Beverly Cleary. Judy Blume. E.B. White. L.M. Montgomery—the Emily books (Emily’s a depressive who wants to be a writer; she was my hero). Around fifth grade I started getting ambitious—Dickens—and by sixth grade I was collecting “great books”—these snazzy editions of the classics that came with their own illustrated magazines explaining the plot and characters—I read Poe and the Brontes and suchlike. But I read everything. I had very highbrow taste. But I’d also devour V.C. Andrews (and make myself ill on it) and Mad Magazine. I remember the first time I saw an episode of “Northern Exposure,” the magical realism of it, I thought wait, I’m allowed to do this? And that was game-changing.

DF: What is your writing process like? Do you listen to music? Outline?

AP: I write in bursts, in a notebook, longhand, generally when I’m in the middle of something else. Then later, when I have enough raw material, I type it up, editing as I go, and then I stitch the pieces together and fill in the gaps. I can’t listen to music. It’s too distracting. And I should learn to outline, but I don’t. I’m very messy. My mind is not well organized. It is a fitful, poorly lit place. Or a compost heap. Let’s call it that.

DF: We’re huge fans of the short story genre here at Writer’s Bone. What is it about the format that appeals to you?

AP: Stephen King calls a short story a kiss in the dark from a stranger. I love that. If I were to state a preference, it would be for long, doorstop-heavy Victorian novels—but with short stories it is possible to achieve a degree of perfection and compression that a novel can’t match. Certain short stories are just complete. A short story is like an egg, self contained, shapely, rounded off. They’re very difficult to do well. The best short story writers understand timing, they know what to leave out, what telling detail should be placed where, how to go for the jugular, how to strike that secret chord, how to sock you in the gut and then pas de bourree offstage leaving you gasping in a dark theater.

DF: How did the idea for Beasts and Children originate?

AP: I read Flaubert’s St. Julien the Hospitaler as an undergrad and internalized it so thoroughly that, 10 years later, I had a vision of animal trophies coming back to life and pursuing their hunter, and I thought it was a stroke of genius. When I reread the Flaubert, I was mortified, because I thought my idea was original. But at that point the title story had mutated so much that it didn’t matter. And honestly, credit for this book has to go in huge part to Jenna Johnson, my editor, whose vision pushed it places, pushed me places, I wasn’t sure I could go. Initially I’d sent her a huge block of unconnected stories, (I was claiming they were “thematically connected,” but they were really just everything I had ever written up to that point). Jenna saw something worth pursuing in four of those stories, and they happened to be interconnected—two were about the Bowmans, and two were about the sisters in Thailand. She asked if I could write more, and link them, and naturally I said yes. Then we traded versions of the manuscript back and forth until it came right. Pilar Garcia Brown at HMH also weighed in with valuable advice and suggestions. As did Ellen Levine, my agent, and my two sisters.

DF: What were some of the themes you wanted to explore throughout the collection?

AP: I was, and am, very interested in the gaps between the stories we tell about themselves—our slanted version of events—and the subtext in those stories of which we’re totally unaware. I wanted to play with a set of stories where characters revise and comment on one another’s experiences, both directly and by showing them living their own lives, with their own delusions. So the power of stories to influence one another, that’s one theme. And of course the question of the destructiveness of the adult world, of adult culture, on the young and on the planet. The question of who adults really are—are they just flailing overgrown children? What does it mean to be an adult? How do we respond to violence, how do we outgrow our wounds; is that even possible? How to be a parent when you’ve been badly parented yourself? Mourning for the shrinking natural world. The deep bond between siblings. Those are some of the themes. Hopefully readers will see others I’m not consciously aware of at the moment.

DF: How much of yourself—and the people you have daily interactions with—did you put into your main characters? How do you develop your characters in general?

AP: There’s a lot of me and my experiences in the book. Both sets of sisters are homages to my own sisters. There are three of us, and I scramble bits of us around in each character. Other characters are completely invented. I develop characters by tuning in to them—it’s kind of like trying to catch a radio station that’s just slightly out of range; I’ll hear snatches of dialogue and then I’ll know I’m onto something. When they start yapping, I take dictation. That’s usually how it starts. Hearing voices. Sometimes it’s a mood, a feeling. But usually, if I can find the voice, then the rest is just a question of examining cause and effect, and how that character would behave in different circumstances.

DF: How long did it take you to complete Beasts and Children?

AP: It depends. With a first book, it’s honestly hard to say, I think. In one sense it took my whole life. I started working on the title story, “The White Elephant,” during a period of intense mourning at Tassajara Zen Mountain Monastery in 2006. That was the inception. Some of the stories I completed in grad school. Some in the first year after my son was born. It wasn’t a linear process at all.

DF: Beasts and Children has garnered rave reviews from the likes of Booklist and Molly Antopol (a Writer’s Bone favorite!). What has that experience been like and what’s next for you?

AP: I’m thrilled and surprised and grateful. Really, this feels like a miracle, and I’ve had a lot of help and support—from Jenna Johnson at HMH, Stephanie Kim, Ayesha Mirza, who work publicity, from Ellen Levine, my agent; from workshop peers and family.

But also, I’ve been so busy trying to raise a kid and teach full-time and write a novel that a lot of this good stuff has been a blur. In Zen, you’re taught not to hang out in bliss, but move on to the next practical thing, and that’s been very much my experience. I would have liked to hang out in bliss for a few minutes, though! I wish I had a talent for celebration, but I don’t. I’m grateful the book has been well received.

I’m currently working on a novel set in Ankara, Turkey. That’s what’s next. Unless HBO calls and offers me a job writing for television. (Seriously, call me.)

DF: What’s your advice to aspiring authors?

AP: Finish your stories! If they’re bad, write better ones, expose the bad ones on a hillside and move on. But train yourself to finish. Also, find a reader who will tell you the truth, a reader who is smart enough and insightful enough to grasp what you’re aiming to do, and who cares enough to read closely and tell you when your skirt, metaphorically speaking, is tucked into the back of your tights. When you find that reader ply them with gratitude and send them burnt offerings and do not let them go because such a reader is the writer’s better half. Truly. And then, and this is very important, listen to them. And rewrite. And read. Read a lot, and risk being read. Though most writers don’t have an especially hard time shoving their manuscripts under people’s noses.

DF: Can you please name one random fact about yourself?

AP: I can do a passable impression of Tom Waits singing “Good King Wenceslas” and I believe that if I do it often enough he will wake up one day and decide to record a Christmas album.

To learn more about Amy Parker, visit her official website.

Full Interviews Archive

Best of 2015: The Top 5 Interviews of 2015

Authors, poets, and screenwriters, oh my!

Our interviews this year ranged from new literary voices to journalists and from comedians to woodworkers (who are also comedians).

Here are our five most popular interviews from 2015. Look for many, many more in 2016!

Author Joe Hill talks to Sean Tuohy about his writing style, his next book, and what books are currently cluttering his nightstand table.

Woodworking 101: The Craft Comes Alive at Nick Offerman's Woodshop

Offerman Woodshop, located in Los Angeles and helmed by comedian and “Parks and Recreation” star Nick Offerman, has been described as “kick-ass” and is filled with extremely talented and skilled artists. With the help of RH Lee, Sean Tuohy learned more about what it takes to design an original piece of art from a slab of wood.

Author On The Rise: 9 Questions With Paula Hawkins

Paula Hawkins, author of The Girl on the Train, talks to Daniel Ford about her love of creativity, her early influences, and how the idea for her popular thriller originated.

Author Enthusiast: 10 Questions With Literary Agent Christopher Rhodes

Literary agent Christopher Rhodes talks to Daniel Ford about how aspiring authors can sensibly chase their publishing dreams.

Royal Writing: 8 Questions With Best-Selling Author Meg Cabot

Best-selling author talks to Stephanie Schaefer about writing, royalty, and those rumors about a “Princess Diaries 3” movie.

Author Enthusiast: 10 Questions With Literary Agent Christopher Rhodes

Christopher Rhodes

By Daniel Ford

My usual correspondence with literary agents tends to involve a lot of weeping and angst, so I’m always thrilled when an agent takes the time to patiently explain the publishing process to our readers.

I connected with Christopher Rhodes, a literary agent for The Stuart Agency, after I heaped praise on his client Taylor Brown’s Fallen Land. It was one of the rare times I gave an agent homework knowing it would result in positive answers (okay, so I slipped him my query letter and a sample chapter, I’m not an idiot)!

Rhodes’ insights into the publishing realm should give aspiring authors all the knowledge they need to sensibly chase their literary dreams.

Daniel Ford: How did you get your start in publishing?

Christopher Rhodes: I grew up in New Hampshire and I worked at a bookstore in high school and this gave me experience enough to land a job at the Borders’ flagship store in New York City at the World Trade Center.

I started working at Borders shortly after it opened in 1996 and stayed through 1999. The three-floor store was insanely busy from 12:00 to 2:00 p.m., Monday through Friday, and I loved working the cash wrap and learning what people were buying. Booksellers gain a wide knowledge of the book market just by seeing and touching books on a daily basis.

While at Borders, I took on the responsibility of maintaining a local interest book kiosk at Windows on the World, the restaurant and bar on the top floors of the North Tower. For a kid from small town New Hampshire who dreamed of living in New York City, this was pretty exciting stuff. Eventually, through friends, I met a man who did publicity for Simon & Schuster and he got me an interview for an entry level sales position there. Off I went to Rockefeller Center and a career was born. From sales I moved upstairs to marketing and worked for the inimitable Michael Selleck before getting hired by literary agent Carol Mann who taught me this side of the business.

A handful of us from that Borders have gone on to really exciting careers in publishing and many of us are still friends. Maybe you’d call it being in the right place at the right time, but I’m also the right person. I fell in love with books as a teenager and I just can’t imagine doing anything else. Publishing was lucky to find me!

DF: Since entering the publishing world, what major changes have you seen?

CR: One major change I haven’t seen since entering the publishing world is that e-books have not beaten up print books and stolen their lunch money.

I started working in the sales division of Simon & Schuster in 1999 and if you had asked me then, I would have told you that the printed book would disappear in three year’s time. There was a fear in the air surrounding the unknown technology and what it would mean to trade book publishing. Turns out the fears were justified, except it wasn’t the e-book we should have been afraid of, it was Amazon.

Lessons are still being learned but I feel like the beginnings of a silver lining have started to appear, especially evidenced in the revolution of the indie bookstore and its power to drive the market. I have two debut novels publishing in January—Taylor Brown’s Fallen Land (St. Martin’s Press) and W.B. Belcher’s Lay Your Weary Tune (Other Press)—and both of them have received enormous pre-sales support from indie bookstores, Brown’s predominately in the southeast where he lives and where the novel is set and Belcher’s predominately in the northeast where he lives and where the novel is set. This kind of specified, regional support is immeasurable and so meaningful to the success of a book. To be able to put an author in front of a bookseller, to have them shake hands and have a conversation, and then to have the bookseller tell her customers about the book, I get chills thinking about this philosophy of salesmanship. I’m very grateful to the publishers my authors are working with who understand the importance of putting a human face behind the books they are selling: St. Martin’s Press, Other Press, Tin House Books. To me, this is a throw back to old school publishing and bookselling, pre-Internet days, and I’m glad it isn’t a major change.

DF: What steps do you recommend an author take when trying to land an agent?

CR: The first step, and the one that is often overlooked by would-be authors who email me asking for representation, is the step of becoming a writer.

Over and over again, in reading submissions and queries, I notice that writers are trying to find an agent too soon in their careers, and this is true for both fiction and nonfiction writers. I would love to believe in the myth:

Unknown writer connects with big name literary agent! Seven- figure deal and film option follow!

That’s all very Lana-Turner-sipping-a-Coke-at-a-Hollywood-drug-store, but it isn’t reality. What I do as an agent is meet an author after she has put in the very hard work—writing, publishing in journals and national magazines, building a marketing platform, winning awards, being noticed for her work, or becoming an expert in her field—and navigate her through the business of trade publishing and get her the best possible deal (which doesn’t always mean the biggest advance).

As an agent, I don’t see myself as a star maker but as a star enthusiast who walks with an author on the last mile to shape her book project into something that will catch an editors eye. Then, if I’m lucky, I get to stick around to manage her career. I also get to be a confidant and business adviser to the writer, but writers make themselves a big deal by being good at what they do and by devoting time and energy to their craft. I read a lot of fiction query letters and nonfiction book proposals and the first things I look at are the author’s credentials. If you are asking me to represent you but have not proven yourself as a writer, I can’t help you.